BK virus-associated nephropathy (BKVAN) after kidney transplantation

In this article we will describe BK (or Human polyomavirus 1) nephropathy.

In 1971, a human polyomavirus was discovered from the urine of a renal transplant recipient whose initials were B.K. This virus has been named ‘BK virus’. BK virus infection usually occurs in early childhood (80%), typically without any symptoms.

The virus then remains dormant (quiet) in the kidneys (and bladder and ureters). Almost all illnesses caused by BK virus occur in those receiving immunosuppression after a kidney transplant. There is detectable BK in the blood and urine of nonrenal solid organ transplant recipients (heart, lung and liver), but in general this has not been associated with impaired kidney (or heart, lung or liver) function in these patients.

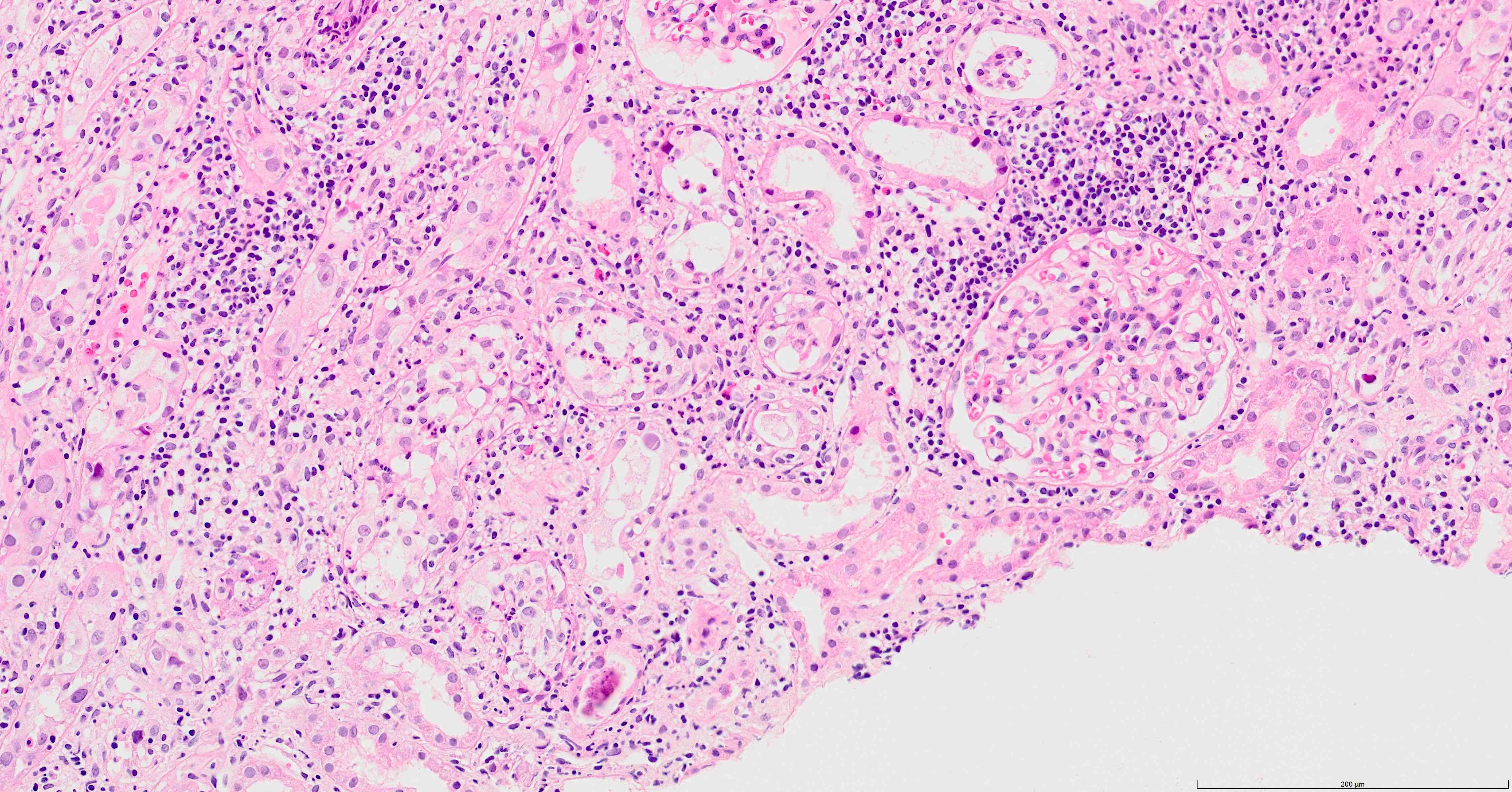

BK viruses in kidney transplant biopsy. Can look like an AIN. Electron microscopy often needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

BK virus is not rare. It is estimated to affect kidney function in 5-15% of renal transplant recipients.

Viruria (virus in the urine) is common following renal transplantation, and testing for this is not helpful. Viraemia (virus in the blood) is less common, and sometimes (not always) associated with interstitial nephritis (inflammation of tubules of the kidney).

So. Let’s discuss BK virus-associated nephropathy (BKVAN) after kidney transplantation in more detail now.

What does BK do to the transplant kidney

BKV associated nephropathy (BKVAN) is a interstitial nephritis that has often been mistaken for rejection, and carries a significant risk of transplant failure. There generally are no extra-kidney symptoms, or other blood tests to suggest a viral infection. The risk of BKVAN is highest in the first year after transplant, but is raised for up to 5 years. Occasionally it occurs later.

So even if the patients has no viral symptoms, measuring blood levels in useful (see below). If kidney function has stopped improving, or is getting worse, BK could be the cause (as well as many other possibilities) and should be looked for.

Risk factors for BKVAN

Donor risk factors

BK virus seropositive donor

Degree of HLA mismatching

HLA C7.

Recipient risk factors

Older age

Male

Recipient race (non-Black)

Diabetes.

Transplant risk factors

Acute rejection episodes

Cold ischaemia time

Delayed graft function

Ureteral stent placement

Anti-thymocyte globulin induction

Tacrolimus and/or mycophenolate-based maintenance immunosuppression.

Screening and diagnosis

BKVAN is almost always associated with significant viraemia, making screening by PCR of blood potentially useful.

This is the protocol used by the Renal Unit at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary:

- First year after renal transplantation: Monthly for 6 months, at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 months, then 3 monthly, at 9 and 12 months

- Thereafter, every 3 months in year 2, and every 6 months in years 3-5, to a total of 5 years of surveillance

- The laboratory will not process a request if <4 weeks has elapsed since the previous result (unless that sample had a positive result).

- In the event of a first positive result, a follow up test in <4 weeks (but not < than 2 weeks) is warranted.

Diagnosis of BKVAN usually requires a renal biopsy. Some centres use urine cytology (looking for BK cells in the urine under the microscope) to identify virally infected cells.

A biopsy may not be necessary if:

- Blood virus levels are low, or falling

- Kidney function is stable.

Management: reduction of immunosuppression

Reduction in immunosuppression is the cornerstone of BKV management. However there is no clear consensus on the viral load above which therapy should be altered. 10,000 copies/ ml is a possible reference point, but as assays are generally not standardised, this can only be considered a rough guide.

The most robust data supports initially reducing or stopping one drug (generally mycophenolate), with later reductions in tacrolimus if viraemia or nephropathy persists. Other options include switching tacrolimus for ciclosporin or even sirolimus.

Corticosteroids are generally continued at the same dose, as other agents are reduced

Renal function and BKV levels should be monitored 2-4 weekly.

Other treatments for BKVAN

These are all unproven and generally not indicated:

- IV IG – contain anti-BKV neutralising antibodies, but there is no robust evidence that it alters the course of nephritis

- Leflunomide – has both immunosuppressive and antiviral activity. The therapeutic dose is uncertain and liver and bone marrow toxicity may occur. There are other significant side effects. There is no good evidence from clinical studies to support its use

- Cidofovir – has modest activity against BKV, but is itself nephrotoxic (toxic to the kidneys). Currently there is only very weak justification for using it or related compounds.

BKVAN and acute rejection at the same time

Surprisingly BKVAN and acute rejection can occur at the same time. And it can be difficult to be sure of, as histological appearances cannot easily distinguish.

Retransplantation

Retransplantation after kidney loss due to BKVAN has generally been successful. It is important to be sure BK viraemia has cleared.

Summary

We have described BK virus-associated nephropathy (BKVAN) after kidney transplantation. We hope it has been helpful.

Other resource

These are review articles: Sawinski, 2015 and Kant, 2022.

This article uses information from these two articles and the EdRen website.

Last Reviewed on 23 January 2024