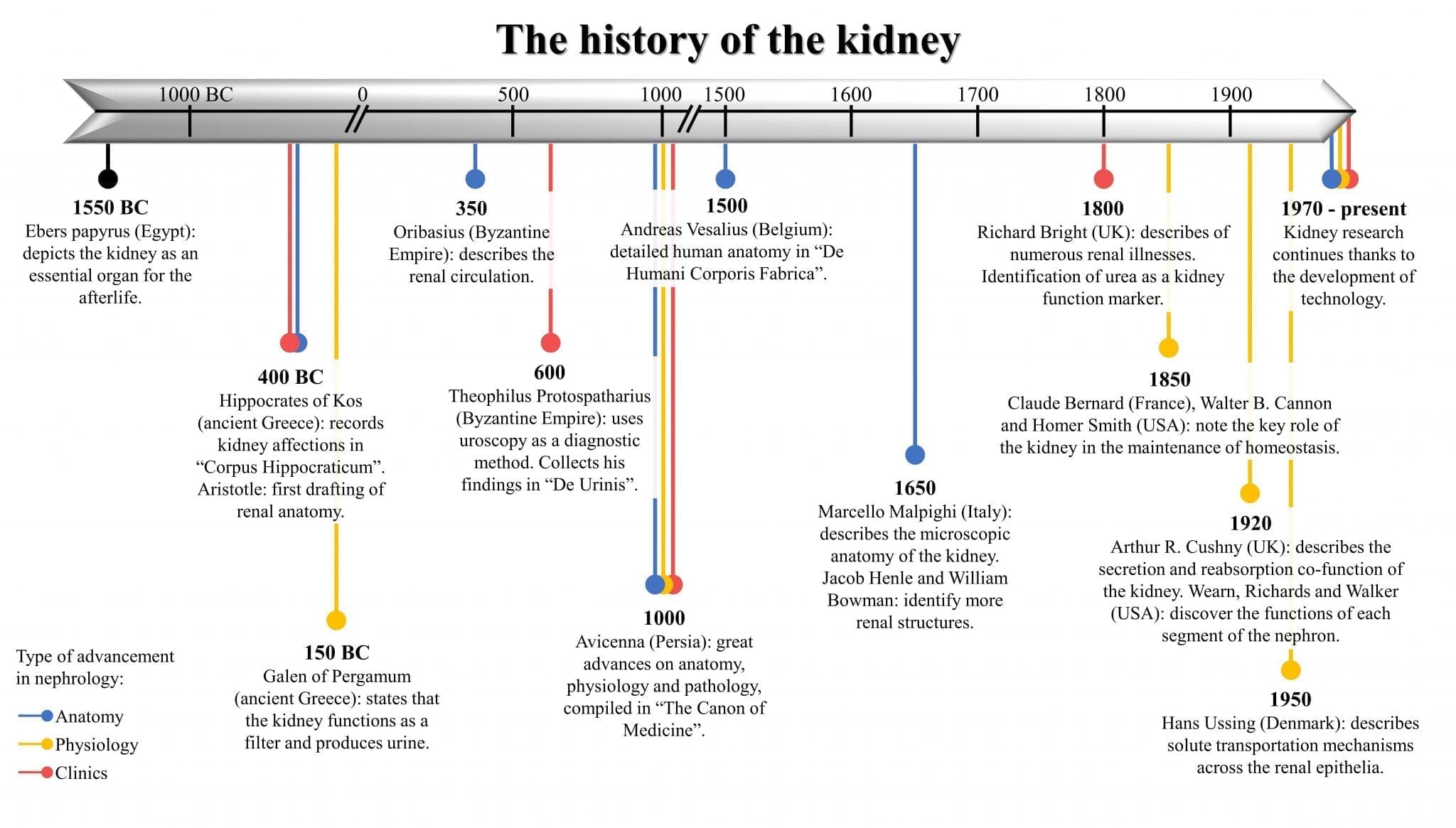

History of nephrology and renal transplantation timeline

This article is a historical timeline of nephrology and renal transplantation. It will largely focus on nephrology.

Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC). Hieroglyphic inscriptions representing the various Egyptian terms for urine.

So. How did it all start? Interestingly, ‘nephrology’ was not a recognised branch of medicine until the early 1960s. Richard Bright and Pierre Rayer – who many consider the founders of modern nephrology – did not use this terminology in the 19th century.

If we look up the word in any medical dictionary, whether English, French or German published during that time (like the one by Morin in 1809), we would find ‘nephrology’ defined as “the section which deals with the anatomy of the kidneys”.

Nephrology was at that time part of urology, in spite of the many advances in knowledge about kidney function and its characteristics during the last three centuries. It was a long incubation period inside urology before nephrology as a definite field in medicine was born.

For a long time, the urologists considered kidney diseases as merely manifestations of urological obstruction, and their pathogenesis as obstructive in the first place. In 1739 a book of urology mentioned that the only treatment needed for anuria was to insert a catheter inside the bladder by a urologist.

Now let’s go back .. to the Egyptians.

Pre-history of nephrology

(from the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC) to end of 1st Century BC)

1550 BC. An ancient description of the kidneys is found in the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, dated to 1550 BC – discovered by the German Egyptologist Georg Ebers (1837-1989). It contained observations made by ancient physicians and included illustrations of human mummies with conditions such as renal cysts or stones. In mummification rites the ancient Egyptians removed all organs from the body except the heart and the kidneys.

The kidney was believed to be a means of judgment in the afterlife, a belief shared by the Jews of Egypt and described in the Old Testament and other ancient writings. The two kidneys were thought to represent good and evil; the right kidney giving a person good advice and the left kidney bad advice.

In the afterlife, the kidneys and the heart would be examined to decide the fate of the soul. A similar concept is found in traditional Chinese medicine, where the two kidneys represent balance and harmony; holding the yin and yang of the body, determine life and death, and are a reservoir of energy.

5th Century BC. Hippocrates of Kos (460-370 BC), the ancient Greek physician, described diseases and conditions of the kidney and urinary bladder in his Corpus Hippocraticum.

4th Century BC. Aristotle (387-322 BC) proposed an anatomy of the human kidney based on empirical observations of fish and birds.

Early history of nephrology

(from start of 1st Century AD)

165-175 AD. Galen of Pergamon (129-218 AD) was one of the most famous Greek physicians; also a philosopher, and surgeon to emperors and gladiators. He was the first to observe that the major function of the kidneys was to produce urine. This is described in Section 13.1 of his On the Natural Faculties (published in three volumes somewhere in 165-175 AD) – and is worth reading. It shows how his (renal) theories were forming, and how he credited previous physicians (like Hippocrates) for their pioneering work.

He even introduced the idea that the kidney functioned as a filter. In fact, the word ‘nephrology’ comes from the ancient Greek ‘νεφρός’ (nephros), which is derived from the word ‘νεφός’ (nephos, meaning cloud), and was a metaphorical description of the kidneys producing urine as clouds produce rain.

Claudius Galenus (Galen)

Claudius Galenus (Galen)

Claudius Galenus (or Galen) was astonishing. He produced more work than any author in antiquity. His surviving work runs to over 2.6 million words, and many more of his writings are now lost.

1590. Microscope invented. With this new doors were opened for the study of renal structure. Strangely the first documented report of microscopy of the kidney was much later, in 1837 (see below).

17th Century

1662. Lorenzo Bellini (1643-1704) was a physician and anatomist from Florence. He published the ‘Exercitatio anatomica de structura et usu renum’ (‘Anatomical Exercise on the Structure and Function of the Kidney) in 1662. He described the (papillary) collecting tubules of the kidney (sometimes known as ‘Bellini’s ducts’). He was 19 years old.

1666. Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694) was an Italian anatomist who worked in Bologna and Pisa, Italy. He made the first microscopical description of ‘glomeruli’ in the ‘De renibus’ a section of ‘De Viscerum Structura Exercitatio Anatomica’. It was published originally in Bologna, Italy in 1666, and in London in 1669.

However, the term ‘glomerulus’ actually belongs, rather than to ancient, to modern Latin, with its first recorded use, according to the Merriam’s Webster and the Oxford dictionaries, dating from the mid-nineteenth century. It appears to be derived from the ancient Latin word ‘glomus’ (plural glomera), third declension, neutral gender, which means ‘a clew, ball made by winding’. There is more information here in the history of the glomerulus.

1672. Matthias Tiling (1634-1685; professor of medicine at Ritlen, Germany) published a treatise on the ‘admirable structure of the kidneys’. The treatise was reissued in 1709 under the title ‘Nephrologia Nova et Curiosa (A New and Curious Nephrology)’ by Johann Helfrich Jüngen (1648-1726), a Frankfurt physician. This may be the first record of the phrase ‘nephrology’. It did not enter common usage.

![view Nephrologia nova et curiosa: quae docet admirandum renum structuram, eorumque usum nobilem ... / Ex principiis de circulari sanguinis motu illustrata à M.T.P. [i.e. Mathias Tiling] Nunc publici iuris facta cura J.H. Junckii.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/thumbs/b33007780_0005.jp2/full/!200,200/0/default.jpg)

Nephrologia Nova et Curiosa, 1709 – probably the first written use of the word ‘nephrologia’

1694. Frederick Dekkers (1644-1720).The presence of protein in the urine was detected by Frederick Dekkers of Leiden in the Netherlands in 1694. It remains to this day the most important and often the most sensitive sign of renal disease. He was the first to describe the boiling test to determine protein in the urine.

![]()

18th Century

1727. Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) a Dutch scientist (also from Leiden), first discovered urea in urine. He was also the first physician to put thermometer measurements to clinical practice. His motto was Simplex sigillum veri: (‘simplicity is the sign of the truth’).

Antoine François (Comte de Fourcroy; 1755-1809), and Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1763-1829) invented the term ‘urea’; and described its chemical composition and physiological meaning. They observed “it is extremely probable that when urea is not separated from the blood, the overload of these substances, and above all urea, is capable of causing diseases”.

1756. Dominico Cotugno (1736-1822; from Salerno, Italy) discovered albuminuria (in a patient with nephrotic syndrome) about a half century before Bright.

Even though Cotugno discovered and described albuminuria, when likening the (pathological) urine to “ovi albuminis persimilem”, strangely this word apparently did not emerge in print until Solon in 1837 (see below).

Stewart Cameron’s ‘Milk or albumin? The history of proteinuria before Richard Bright’ (2003) tells the story of the early descriptions of albuminuria before Bright.

Apart from those two advances, we do not find much data related to nephrology during that century.

19th Century

1803. The word ‘nephrology’ – was included in the French dictionaries of Boiste in 1803, and Morin in 1809 (as ‘néphrologie’).

1817. William Prout (1785-1850; English physician/chemist), made the first pure preparation of urea from urine.

1821. Jean-Louis Prevost (1790-1850; Geneva) and Jean-Baptiste Dumas (1800-1884; Paris) clarified the events following nephrectomy and called it ‘uraemia’. They showed that the blood urea of binephrectomised animals was high and chemically identical to that of urine.

There observations were published in this paper: Prévost JL, Dumas JB (1823). Examen du sang et de son action dans les divers phénomènes de la vie. Ann Chimie Physique Paris 23: 190-104. It was within a report of a meeting in Geneva held on Nov 15th 1821. Was this the first ‘renal meeting’?

1827. Richard Bright (1789-1858), a London-based physician, excelled at making meticulous clinical observations and correlating them with careful postmortem examinations.

The results of his wide-ranging research first appeared in Reports of Medical Cases (1827), in which he established oedema (swelling) and proteinuria (the presence of albumin in the urine) as the primary clinical symptoms of the serious kidney disorder that bears his name – Bright’s disease, or ‘nephritis’.

This is considered one of the first publications which enabled nephrology to become a distinct branch of medicine.

Interestingly Bright also first linked renal disease to left ventricle hypertrophy, in 1836. He related hypertrophy to an increased resistance to blood flow in the small vessels of the kidney due to the some altered condition of the blood.

1837. Gabriel Valentin (1810-1883; German; worked in Bern) poorly documented paper, published in1837, was the first report of microscopy of the kidney: Valentin G: Examen Microscopique des Granulations des Reins, Repertorium für Anatomy Physiologiches, vol. 2, Heft 2, s.290, 1837.

1838. Ferdinand Martin-Solon (1795–1856), in Paris, first coined the term ‘albuminuria’ in ‘De l’albuminurie ou hydropisie causée par maladie des reins’ (Béchet Jeune, Paris, 1838). This work included, as well as extensive material on urine testing and chemistry, five coloured plates depicting diseased kidneys.

1840. Pierre Rayer (1793-1857), also in Paris, first described inflammation of the kidney as ‘nephritis’. Between 1837 and 1841 he published a three-volume book on diseases of the kidney titled ‘Traité des maladies des reins’. He and others at that time attempted to classify renal diseases. Rayer’s huge contribution to nephrology is described in this 1991 paper in Kidney International.

In ‘On diseases of the kidney’ (British and Foreign Medical Review, 1840), we can read great interactions between Bright, Solon, Rayes and others.

1842. Carl Ludwig (1816-1895; Marburg, Germany). Very little was known about the physiology of the kidneys until the middle of the 19th century. The turning point came in 1842 when the physiologist and physician Carl Ludwig presented a theory about a two-step process (filtration and reabsorption) leading to the excretion of urine. He also showed the relationship between the blood pressure and glomerular filtration.

1842. Sir William Bowman (1816-1892; Birmingham/London). Bowman, at the young age of 25 years, described his eponymous capsule of the glomerular capillary tuft; and demonstrated its continuity with that of the basement membrane of the connecting tubule. This is a key component of the nephron. He presented his findings in 1842 in his paper “On the Structure and Use of the Malpighian Bodies of the Kidney” to the Royal Society.

In this paper, Bowman also proposed that urine formation begins with glomerular secretion. At nearly the same time in Marburg, Carl Ludwig, unaware of Bowman’s findings, proposed that urine formation begins with glomerular filtration followed by tubule reabsorption. The latter theory was later proven to be correct.

In the period between 1830 and 1860, Bowman and Ludwig both worked closely on the glomerulus and its connection with the proximal tubule.

1843. Johann Franz Simon (1807–1843; Berlin) described all the features of the urinary sediment, including casts (see his illustration middle right, arrowed) in his book of 1843: Beiträge zur physiologischen und pathologischen Chemie und Microskopie, Berlin, 1843,

“ [they are] composed of an amorphous matter, resembling coagulated albumin….they are derived from the epithelium investing the ducts of Bellini”.

![Figure 5: Franz Simon’s illustration of all the features of the urinary sediment, including casts (middle right, arrow) from his book of 1843 Beiträge zur physiologischen und pathologischen Chemie und Microskopie, Berlin, 1843 [50].](https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/cclm-2015-0479/asset/graphic/j_cclm-2015-0479_fig_005.jpg)

There is more about Simon and many other early microscopists in Stewart Cameron’s ‘A history of urine microscopy’ (2015).

1869. Edwin Klebs (1834-1913; German-Swiss microbiologist) – described and introduced the term ‘glomerulonephritis’.

1878. Claude Bernard (1813-78; Paris-based physiologist). His main contribution to physiology and medicine is probably the creation of the concept of ‘milieu intérieur’ and its constancy, which was later called ‘homeostasis’ (the latter term being coined by Walter Cannon).

Claude Bernard wrote “For the animal there are really two environments: an ‘external environment’ in which the organism is placed, and an ‘internal environment’ in which the elements of the tissue live …. the fixity of the internal environment is the condition of free and independent life”. This concept is such an important one that the term ‘milieu intérieur’ is still kept in French in English language publications.

1879. Theodor Langhans (1839-1915; German pathologist) – first used a terminology for ‘glomerulonephritis’ to describe the inflammation of the kidney secondary to glomerular injury. Langhans is also remembered for his discovery of multi-nucleated giant cells that are found in granulomatous conditions, and are sometimes referred to as ‘Langhans giant cells’.

1898. Sándor Korányi (1866-1944; physiologist and physician from Budapest) developed physicochemical tests – e.g. to measure the kidney’s ability to maximally concentrate the urine – to estimate renal function. In parallel with the deterioration of renal function, he found characteristic changes in the freezing point depression of urine, which he termed ‘hyposthenuria’. On the basis of these findings, he was the first to introduce the functional concept of renal insufficiency.

1898. Hermann Rieder (1858–1932; a radiologist and pathologist from Leipzig, Germany) and Auguste Sheridan Delépine (1855-1921; an originally Swiss-French bacteriologist and pathologist who worked in Manchester, England) – published an ‘Atlas of Urinary Sediments’ (Atlas der klinischen mikroskopie des harnes), which helped to assist identification of casts and crystals.

Hermann Rieder

Early 20th Century

In the first half of this century there were multiple advances in this branch of medicine.

1924. Hermann Braus (1868-1924; professor of anatomy at the University of Heidelberg) introduced the term ‘nephron’ (derived from the ancient Greek word for kidney, ‘nephrós)’ in German.

1927. Charles Oberling (1895–1960; French pathologist and oncologist) working in Strasbourg, described the juxtaglomerular apparatus in a brief two-page report.

1929. Karl Zimmerman (1861-1935; German anatomist and pathologist) working in Bern, described the maculla densa.

This improved knowledge of the ultra-structure of the kidney helped physiologists understand the function of the kidneys better – contributing to continuous progress in the field.

Excretory function of the kidney

1928. Donald Van Slyke (1883–1971; Dutch-American biochemist, Long Island) – introduced the definition of renal clearance. His work was extended by Homer Smith from New York in the period 1930-1932; when the latter proved that creatinine clearance was close to insulin clearance, in order to calculate the glomerular filtration rate.

1945. Homer Smith (1895-1962; New York physiologist) – published an article that demonstrated that para-aminohippuric acid is the most suitable agent for the evaluation of renal plasma flow in both humans and dogs; in addition, the paper provided detailed methodology that is still in use today.

1945-46. Robert Pitts (1908-77; New York physiologist) – published two landmark papers. The first paper, published in 1945, addressed and successfully resolved the problem of the nature of the mechanism by which renal tubules acidify the urine. The second paper, published a year later, described renal excretion of bicarbonate.

The kidney as an endocrine organ

1898. Robert Tigerstedt (1853- 1923; Finnish professor of physiology, Karolinska Institute) – and his assistant Bergman analysed the effect of renal extracts on arterial pressure. They discovered the presence of a pressor compound in the renal tissue of the rabbit, and based on its origin, they named it ‘renin’. In other words, they first described renin as a factor affecting blood pressure and secreted by the kidney.

1938. Irvine Page (1902-91; American physiologist, Cleveland Clinic) – working with Helmer and Kohlstaedt, investigated the mechanism of action of renin. They concluded that renin was an inactive enzyme that was activated by yet another enzyme, belonging to the kinase group. This plasma protein compound was named ‘renin activator’.

1938-45. Norbert Goormaghtigh (1890-1960, Belgian pathologist) – related the synthesis of renin to the juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA).

1957. Leon Jacobson (1911-1992; Chicago-based physician) – established that the kidney produces erythropoietin.

1952. GW Sobel – extracted and isolated (and named) urokinase from urine. It is an activator of plasminogen to plasmin. Urokinase (as tPA) is effective for the restoration of flow to intravenous catheters (e.g. dialysis) blocked by clotted blood or fibrin. This is why it is important in nephrology.

1966-1971. Hector Deluca (Wisconson) and Egon Kodicek (1908-82; Prague/Cambridge) – discovered the structure of vitamin D and the mechanism of its activation by the kidney; and the role of parathormone and hypophosphatemia in its activation.

Further research on renal function

1944. Nils Alwall (1904-96; University of Lund, Sweden) – performed the first systematic aspiration needle biopsies of the kidney in 1944, but did not publish his results until 1952 because of an early death which led him to abandon the technique.

1949. Jean Oliver (1889-1976; Stanford/Long Island; American pathologist) – concentrated his research on nephrons and described the relationship between their loss and the progress of the renal failure. In 1949, Oliver gave the Ramon Guiteras Memorial Lecture entitled “When is the Kidney not a Kidney?”. He stressed that nephrons were a heterogeneous population, differing in length and shape (and therefore function), throughout the kidney as opposed to a homogenous filtration unit.

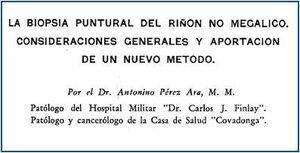

1950. Antonio Pérez Ara (Cuban) – carried out the first percutaneous renal biopsy. He began performing biopsies in 1948, and published a series of findings from 8 patients in a local journal in 1950: Pérez Ara A. La biopsia puntural del riñón no megálico. Consideraciones generales y aportación de un nuevo método. Bol Liga contra Cáncer 1950; 25: 121-47.

1951. Poul Brun (1914-2014) and Claus Iversen (Copenhagen) – described the technique of the kidney biopsy by a needle (Brun and Iverson, 1951). This later led to an improvement of understanding of the clinico-pathological basis of renal disorders.

1955. Robert Platt (1900-1978; Manchester; later President of Royal College of Physicians) – proved the presence of ‘Bright islands’ in the kidneys which are formed of healthy nephrons compensating for the function of the damaged ones.

1960-75. Neal Bricker (1927-2015) – realised the importance of Oliver and Platt’s work. He characterised further the events which take place in the compensating nephrons in CKD, and called it his ‘intact nephron hypothesis (INH)’. This stated as CRF advances, kidney function is supported by a diminishing pool of functioning (or hyperfunctioning) nephrons, rather than relatively constant numbers of nephrons, each with diminishing function.

This means that when nephrons are lost through disease, the least affected or remaining nephrons undergo remarkable adaptive physiologic responses; resulting in nephron hypertrophy and hyperfunction that combine to compensate for the acquired loss of renal function.

Therefore, regardless of the nature of the disease, or the nature of the solute under consideration, the chronically diseased kidney is able to maintain external balance far into the course of the disease.

1975-85. Barry Brenner (Boston) – showed the relationship between hypertrophy of the kidneys due to the increase in the glomerular filtration rate, as in diabetes; and the development of the hyalinosis of the glomeruli.

Later Broyer et al proved in rats that restriction of protein intake delayed the deterioration of glomerular filtration rate, which had an impact on the management of renal insufficiency in the past. Low protein diets are now rarely recommended.

1986. Joseph W. Eschbach (1933-2007; Seattle-based physician) – John W. Adamson, and colleagues in the U.S., and Chris Winearls and colleagues in England, establish that recombinant human erythropoietin (EPO) can correct the anaemia of chronic renal disease.

Renal replacement therapy (RTT)

1933. Yuri Yurijevich Voronoy (1895-1961). Working in some obscurity, Voronoy performed six human kidney allografts between 1933 and 1949 – the kidneys being transplanted into the thigh.

The first transplant happened on the April 3rd, 1933. The first ‘successful’ one, also was the first human-to-human kidney transplant. The recipient was a 26-year old woman who was admitted in a uraemic coma after swallowing mercury chloride in a suicide attempt. Voronoy published in 1936, in a slightly obscure Spanish journal.

Voronoy’s publication in El Siglio Medico, 1936

Note. It is very difficult to state who carried out the first human renal transplant. Some would say Voronoy, others the pioneers that came later (see below). This is because it depends on whether you are specifying the first successful one (or any), the type (e.g. intra-abdominal or not), or whether the recipient had AKI (who may have recovered anyway), CKD or ESRF (who would not).

1940. Gordon Murray (1894-1976; Toronto-based surgeon) – used heparin for the first time in human patients. Murray also developed a haemodialysis machine and performed the first successful haemodialysis in a human in North America, in 1946 (see below). He also contributed to the development of transplantation (see History of Renal Transplantation).

Gordon Murray

Gordon Murray

Murray’s haemodialysis machine

Murray’s haemodialysis machine

1941. Eric Bywters (1910-2003) and Desmond Beall (1910-99) – London-based physicians. It is unclear when the concept of AKI was first recognised. A landmark article was first published in 1941 by Eric Bywaters and Beall during World War II. They reported four cases of crush injury followed by impaired renal function. In addition to the description of the natural history of renal injury, they examined the pathology of the kidney and demonstrated widespread tubular damage and pigmented casts inside the tubular lumen

1943. Willem Johan ‘Pim’ Kolff (1911-2009) – studied medicine in his hometown at Leiden University, and continued as a resident in internal medicine at Groningen University. One of his first patients there was a 22-year old man who was slowly dying of renal failure.

This prompted Kolff to perform research on artificial renal function replacement. Also during his residency, Kolff organized the first blood bank in Europe (in 1940). During World War II, he was based in Kampen, where he was active in the resistance against the German occupation.

In 1940, while taking care of casualties after the German invasion of the Netherlands, his interest in acute renal failure further increased. And, in 1943, he and Hendrik Berk introduced the rotating drum hemodialysis system (Kolff, 1944). This was the first haemodialysis machine.

This used cellophane membranes and an immersion bath and the first recovery of an acute renal failure patient treated with haemodialysis was reported. Working under Nazi scrutiny in the occupied Netherlands, he constructed the first machine out of common items, including a washing machine, orange juice cans and sausage skins.

1946. Gordon Murray – treated the first patient with ARF in North America with a haemodialysis machine he had developed. He also developed an AV shunt. He proceeded to treat 1,500 people in kidney failure between 1946 and 1960 (using his dialysis machine and shunt); as reported to the First International Congress of Nephrology held in Evian/Geneva in September 1960. This was a staggering achievement.

1947. Nils Alwall (1904-96); University of Lund, Sweden) – developed a new haemodialysis system with a vertical stationary drum kidney and circulating dialysate around the membrane.

It appears that Kolff, Murray and Alwall developed artificial kidneys at about the same time, unaware of each others’ work, partly due to the time period (WWII) when the research happened.

Kolff, Murray and Alwall used dialysis machines for the treatment of acute renal failure. The technique of dialysis improved over the years from many aspects including use of heparin, dialysers with semipermeable membranes, and control of sodium and potassium homeostasis. These advances contributed to the safety and efficiency of dialysis for acute (ARF, later AKI) and chronic renal failure (CRF, later CKD).

1948. Alwalls other contributions. Alwalls contribution to nephrology did not stop there. Stanley Shaldon (2003) has emphasised the role of Alwall, with Murray, of developing the AV shunt. The original idea of a bypass to maintain the patency of indwelling arterial and venous catheters was developed by Nils Alwall in 1948 and published in 1949 (Alwall and Bergsten, 1949). The shunt was a key advance that made longer term dialysis possible.

Alwall was also responsible for applying hydrostatic pressure to achieve ultrafiltration, and pioneering the renal biopsy.

1950. Richard Lawler (1895-1982; Chicago surgeon) – carried out the first successful intra-abdominal deceased donor renal transplant in a patient with CKD. It was carried out on 17th June. He removed a kidney from a patient with cirrhosis who had died of liver disease, and placed it into his patient, Ruth Tucker (44 years, below), who had polycystic kidney disease (removing one of them at the same time) (Lawler, 1950). The kidney lasted 53 days, and was removed after 10 months.

Dr. Richard Lawler, Dr. James West, and Dr. Raymond Murphy

1951. Jean Hamburger (1909-92; French physician) – and his young assistant, Gabriel Richet, left the large and undifferentiated medical service of Professor Pasteur Vallery Radot at the Hôpital Broussais to establish a renal specialty unit at the Hôpital Necker in Paris; thus creating the first department of nephrology in France.

In December 1952, working with the urologist Louis Michon at the Necker, transplanted a kidney from a live volunteer donor (Michon, 1953). The kidney, which was donated to a 16 year carpenter Marius Renard from his mother, functioned well and for 3 weeks before being rejected by the non-immunosuppressed recipient.

In 1953, Hamburger proposed the term ‘nephrology’, based on the French word ‘néphrologie’; from the Greek νεφρός / nephrós (kidney) combined with the suffix -logy, ‘study of’. Before then, the specialty was usually referred to as ‘kidney medicine’. It became a favoured term in the early 1960s.

1955. Joseph Murray (1919-2012; Boston) – working with the physician John Merrill (1917-1984) – performed the first successful identical twin-to-twin transplant in the USA, on Richard (recipient) and Ronald (donor) Herrick on December 23rd 1954. He was assisted by Dr J Hartwell Harrison (urologist).

Murray shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990 with E. Donnall Thomas for”their discoveries concerning organ and cell transplantation in the treatment of human disease.”

Their work between identical twins was followed by allografting from related and unrelated donor and recipient groups.

First congresses

As early as the mid-1950s the concept of holding an international meeting and creating a new international society was discussed repeatedly within the small core of the Hamburger group. Small national societies of relevance to kidney disease were emerging slowly in Europe.

These included the Societé de Pathologie Renale in 1948–49 (the first national society, and predecessor of the Societé de Néphrologie which formed in 1958-59), the UK’s Renal Association in 1950, the Scandinavian Society for Kidney Research in the late 1950s (but which never really met), and the Societa Italiana di Nefrologia in 1957 (the first European Society to incorporate the word ‘nephrology’ in its title). Jo Joekes, a London-based physician (and secretary of the Renal Association, 1956-61) was involved in the early organisation of the first congress (see below).

With the possible exception of the founding of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs (ASAIO) in 1955, there was no comparable organizational movement underway in the United States. Programmes (and politics) of relevance to the kidney were resident mainly within the Nephrosis Foundation or the Renal Section of the Council on Circulation of the American Heart Association during the late 1950s and early 1960s (a fact that can trace its historical origin to the close association of Homer Smith with both the New York and American Heart Associations and the field of cardiology).

There is more information on the history of renal congresses and conference in a Forty year history: 1960-2000 in Kidney International.

1960. First congress. The First International Congress of Nephrology (Premier Congrés International de Néphrologie) was held in Evian (France) and Geneva (Switzerland), and led to the establishment of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN), also in 1960. Jean Hamburger was elected as the first president.

400 delegates attended.

It was a real milestone for nephrology to become a distinct branch of internal medicine. The scientists of anatomy and physiology besides clinicians had one goal to pursue: better understanding of the function of the kidney. During that congress they agreed, for the first time, to draw a tortuous nephron figure instead of the straight one known before.

The participants also agreed to consider the functions of all nephrons as one integrated unit, and drew a detailed figure of renal structure. As well as this, they developed the concept of acute renal failure, with its clinical and anatomical manifestations, to further understand its pathogenesis.

During the same congress, Scribner presented the experience of four patients treated by haemodialysis and introduced the possibility of the wide spread use of this technique in renal replacement therapy.

1960. Belding Scribner (1921-2003; University of Washington, Seattle). Long-term haemodialysis for ESRF first became possible with Scribner’s further development of the AV shunt (Teflon) as vascular access for haemodialysis. ESRF could now be treated for long periods with haemodialysis – not just as a bridge to transplantation. This led to the spread of haemodialysis around the world.

Over the next 4 years, many of the advances in dialysis occurred in Seattle. These included recognition and treatment of complications such as malignant hypertension, gouty episodes due to uric acid accumulation, subcutaneous calcification, anemia, iron overload, and peripheral neuropathy.

Technical advances included improving the shunt, and in collaboration with Professor A.L. Babb, development of a proportioning system to make dialysate from concentrate and water, and the first automated home haemodialysis machine.

Drs Boen and Tenckhoff developed automated peritoneal dialysis equipment and peritoneal access devices.

1962. Seattle. The world’s first outpatient dialysis centre, the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center, was established.

1967. Jean Dausset (1916-2009; Paris-based immunologist) – discovered the HLA system which helped in the later success of transplantation, and the progress of immune techniques and genetics.

Dausset received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1980 along with Baruj Benacerraf and George Davis Snell for their discovery and characterisation of the genes making the HLA system, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

1976-79. The new technique of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) was developed.

1976. Robert Popovich (1939-2012; scientist) and Jack Moncrief (physician), working in Austin, Texas, published an abstract describing the principles of continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD). Two years later, they published their first results of CAPD (Popovich, 1978).

Bob Popovich (right) and Jack W. Moncrief (left) accept the American Kidney Fund National Torchbearer Award in 1989.

1978. Dimitrios Oeopolous (1936-2012; Toronto) – introduced PVC bags, rather than glass bottles, to contain the dialysate.

His advance caused enormous growth in utilisation of the PD technique. The number of dialysis units in Europe providing CAPD was 0 in 1977, but had increased to almost 160 by 1979 (Jacobs, 1981). In this paper,the first clinical results were published – but the results were rather discouraging. In 1979, the combined 2-year patient and technique survival in 1728 patients was only 32%.

In 1980, he started a journal titled Peritoneal Dialysis Bulletin – which was later changed to Peritoneal Dialysis International – aimed at spreading knowledge about PD worldwide.

1979. Karl Nolph (1937-2014; Columbia, Missouri) – introduced the light titanium connector, in order to reduce peritonitis rates. He wrote 461 articles.

1981. First national conference on CAPD – was organised in Kansas City (Nolph, 1981)

CKD and AKI classifications based on renal function

2002. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) classification (based on eGFR)

In 2002, the U.S. National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) clinical practice guidelines (Levey et al) provided for the first time a working definition of CKD (a name that replaced chronic renal failure, CRF) irrespective of the cause of kidney disease. It was based on the presence of kidney damage or a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 ml/min for more than 3 months.

The proposed classification system – with 5 stages of CKD – was based on the severity of the disease derived from the level of kidney function, irrespective of diagnosis. The level of kidney function was recommended to be determined from the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), rather than just that of the traditional serum creatinine level from which the eGFR is calculated.

This classification system was quite dissimilar to previous systems based on pathology; and a movement towards a focus on prevention of worsening of renal function – rather than precise pathological diagnosis.

2004. Acute kidney injury (AKI) classification (RIFLE system)

In May 2004, a new classification for AKI (a name that replaced acute renal failure, ARF) called RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage kidney disease) was proposed by Bellomo et al; in order to define and stratify the severity of acute kidney injury (AKI).

This system relies on changes in the serum creatinine (SCr) or glomerular filtration rates and/or urine output, and it has been largely demonstrated that the RIFLE criteria allows the identification of a significant proportion of AKI patients hospitalised in numerous settings, enables monitoring of AKI severity, and is a good predictor of patient outcome.

RIFLE has been superseded by other systems based on it: AKIN, KDIGO and NICE.

Summary

We have described a history of nephropathy and renal transplantation timeline. We hope you have found it interesting.

Other resource

What did the ancient people know about kidneys? (quite alot actually)

Last Reviewed on 6 July 2024