What causes acute interstitial nephritis (AIN)?

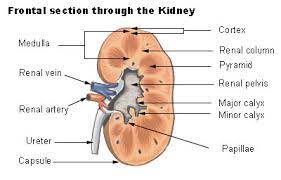

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is an acute inflammation of the ‘tubulo-interstitium’ of the kidney. This is mainly in the medulla (inner area) of the kidney. In other words, it is not in the glomeruli (mini-filtering units), which are mainly in the cortex (outer area) of the kidney. It is usually caused by a hypersensitivity (allergic) reaction to a medication. Autoimmune diseases and infections are less common causes.

Interstitial nephritis was first described in 1898 by William Thomas Councilman, chief pathologist at Brigham Hospital, who noted interstitial abnormalities on autopsies of patients with streptococcal infections.

So. What causes acute interstitial nephritis (AIN)?

70-75% of cases are drug-induced with >250 known triggering medications. Common classes include antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors, diuretics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; cause 45% of drug induced cases), and immunotherapy.

If related to medication, AIN usually occurs 2 or more weeks after starting the drug.

It also occurs in inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis, Sjogren syndrome, Kawasaki disease, IgG4-related diseases, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis with uveitis (TINU) syndrome.

5% are due to infection, of all types; bacteria (e.g. streptococci, leptospirosis, syphilis, TB), viruses (HIV, EBV, CMV, hantavirus, herpes simplex; BK especially in kidney transplant patients), protozoa (toxoplasmosis), rickettsia (Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever) and fungi. Some malignancies can also cause AIN (e.g. lymphoma).

AIN usually presents with acute kidney injury (AKI), or sub-acute (i.e. over weeks) loss of kidney function. The classic ‘hypersensitivity triad’ of rash, fever, and eosinophilia occurs rarely (<10%). Nephrotic syndrome is rare presentation and may be caused by NSAIDs.

Definition

AIN is a pathological pattern of kidney inflammation (i.e. shown on a kidney biopsy), which localised to the tubulo-interstitium and usually triggered by medication.

Clinical presentation

- Acute kidney injury (AKI, most present with this; 40% requiring dialysis – e.g. decreased urine output, nausea or vomiting, raised blood pressure; ankle swelling, shortness of breath or rapid weight gain (caused by extra fluid in the body)

- Microhaematuria (blood that can only be seen in under a microscope) – 65%; macrohaematuria (blood that can be seen) – 5%

- Arthralgia (joint pain) – 45%

- Fever – 35%

- Skin rash – 20%

- Nephrotic syndrome (rare).

Typical rash of AIN

How is acute interstitial nephritis diagnosed?

Your doctor will ask you about your medical history, especially what medicines you take. These investigations will be done:

- FBC (35% have eosinophilia), ESR and CRP

- U+E

- Urinary dipstick: mild-moderate proteinuria (protein in urine); raised white cells (80%)

- MSU: pyuria (white cells in urine, especially eosinophiluria)

- uACR: 90% have non-nephrotic proteinuria, 2-3% nephrotic-range proteinuria 2-3%, and 1% nephrotic syndrome

- Kidney ultrasound

- Kidney biopsy.

Clinical diagnosis relies on maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion and performing a kidney biopsy to obtain tissue for histological (microscope) diagnosis. Typical features include interstitial immune infiltrate, eosinophils, and tubulitis. These terms mean signs of the immune system attacking the tubules of the kidney.

Kidney biopsy showing AIN. Note the dark dots, which are lymphocytes (a form of white cell) around the normal glomerulus. Most of the inflammatory cells are lymphocytes.

Can AIN be prevented or avoided?

In most cases, there is nothing you can do to prevent interstitial nephritis. You can reduce your risk of getting it by avoiding medicines that can cause the condition. This is not easy as many are common drugs. Fortunately they rarely lead to AIN.

Treatment

AIN is caused by an underlying problem. Treatment depends on what is causing the condition. If the problem is an infection, your doctor will treat the infection. If a medicine is causing it, you will need to stop taking the medicine.

In some cases, steroids (medicines that reduce inflammation, e.g. prednisolone) may be used.

This is because, although prospective randomised trials (this means good scientific evidence) in AIN are lacking, retrospective studies suggest that early steroid treatment (within 7 days after diagnosis) improves the recovery of renal function.

Dialysis is sometimes necessary, usually in the short-term.

Prognosis (outlook)

AIN usually resolves once a triggering medication is discontinued. Steroid therapy may lead to a quicker recovery of kidney function.

Renal impairment may persist for weeks or months, but recovery usually occurs within the first 3 months. AIN with renal impairment for greater than 3 weeks carries a worse prognosis.

One series revealed that 25% of patients with AIN ultimately returned to their baseline renal function, whilst 5% required long-term dialysis and/or a kidney transplant.

It is estimated that 50 % of patients will not fully recover their baseline renal function after six months (Modelina, 2021) – i.e. will have some residual renal impairment (CKD) after an AIN episode.

Summary

We have described what causes acute interstitial nephritis (AIN). We hope it has been helpful.

Other resource

These are review articles: Praga, 2010; Joyce, 2017; Schurder, 2020; and Finnigan, 2023.

Last Reviewed on 28 January 2024