What is mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis?

Mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN) is one of the 7 types of chronic glomerulonephritis (GN) but one of the least common types.

They are all ‘autoimmune diseases’ where the immune (defence) system attacks normal tissue in the kidney (including the glomerulus). Why and how they occur is unclear. MCGN is also known as ‘membranoproliferative’ (or ‘lobular’) glomerulonephritis.

Typical renal biopsy on electron microscopy in Type I MCGN.

MCGN is an uncommon cause of nephrotic syndrome, compared to FSGS and MCD. It can be divided into two types: primary (no known cause) or secondary (with a range of causes, see below).

Primary forms affect children and young adults between ages 8 and 30 (rare under the age of 5 years) and account for 10% of cases of nephrotic syndrome in children.

Secondary forms tend to affect adults > 30 years. Men and women are affected equally. There are a small number of familial cases, suggesting genetic factors play a role in at least some cases.

In mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, immune complexes (antigen-antibody combination) are deposited in two parts of the glomerulus (see below).

To make things more confusing [“think we get that” CKDEx Ed] about a complicated disease, according to the kidney biopsy appearances, MCGN can also be divided in three subtypes, Type I-III (also see below).

What causes MCGN?

MCGN is not caused by a single disease. It has different types, and many causes:

- Primary MCGN. This type of MCGN means that the disease happened on its own without a known or obvious cause. It is presumed to be an autoimmune disease, i.e. caused by your own immune (defence) system attacking the glomeruli within the kidney

- Secondary MCGN. This type is secondary to some other disease (autoimmune or otherwise)

- Other autoimmune disorder – e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, cryoglobulinaemia

- Chronic infection – e.g. infective endocarditis; HIV, hepatitis B (HBV) or C infection (HCV); chronic abscess, ventriculoatrial shunt (‘shunt nephritis’); malaria, schistosomiasis

- Blood disorder – e.g. monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significant (MGUS), AL amyloidosis, light and heavy chain deposition diseases, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), lymphoma, multiple myeloma

- Other disorder – sickle cell disease, chronic liver disease, complement deficiency.

Note. Mixed essential cryoglobulinemia associated with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) is especially linked to MCGN. It is an example of an overlap between an infection and a autoimmune condition. In other words, it is thought that the infection ‘sets off’ an autoimmune condition – in ways we do not yet understand.

Symptoms

MCGN can present in many different ways. These include:

- Nephrotic syndrome (50%). This is the commonest presentation. It shows itself as ankle/leg/peri-orbital oedema (swelling), fatigue, and appetite loss. High blood pressure is a common feature. But MCGN can present in other ways:

- Macroscopic/microscopic haematuria (30%). Intermittent macroscopic (visible) haematuria (blood in the urine) can follow an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), similar to IgA nephropathy

- Nephritic syndrome (15%)

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD) – some of these patients go to develop CKD5 (kidney failure) and need dialysis, and/or a kidney transplant (and MCGN can come back in the new kidney)

- Acute kidney injury (AKI; rapid onset kidney failure) – these patients are quite unwell and in hospital, and may need dialysis.

Type II MCGN (dense deposit disease) may occur in association with two other conditions, either separately or together: acquired partial lipodystrophy (APD) and eye abnormalities like macular degeneration.

Partial lipodystrophy is a particular facial (and body) appearance, with a narrow face (due to an absence of fat in the skin) as in this picture.

Partial lipodystrophy

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of MCGN is made through medical assessment by a kidney specialist (nephrologist), blood and urine tests, and a kidney biopsy. High cholesterol levels are common as well.

Blood tests should also include ones of the immune system (e.g. cryoglobulins, complement 3 and 4, and C3 nephritic factor); and tests looking for an underlying cause – e.g. Hep B/C and HIV; and blood cultures (for infective endocarditis).

70-80% of patients have low complement levels, and are a feature of MCGN. This is called ‘hypocomplementaemia’.

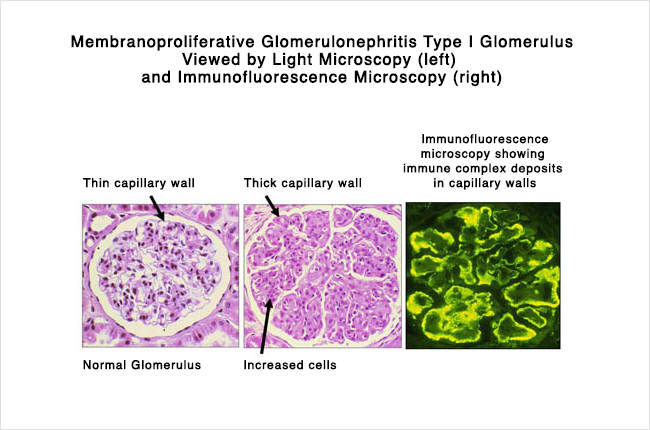

As shown in the pair of light microscope pictures of a glomerulus on a kidney biopsy (on the left) above, MCGN is characterised by

- A thickened capillary (tiny blood vessel) wall (called the glomerular basement membrane, GBM). This explains the ‘-capillary’ part of the name mesangiocapillary

- An increase in the number of cells (proliferation) in the middle of the glomerulus (mesangium). This leads to the ‘mesangio-‘ part of the name mesangiocapillary.

As well as classifying MPGN by being primary/secondary, it is also classified into types I, II, and III, based on the findings on a kidney biopsy.

- Type I mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (classical). This the commonest type (70-80%). 50% of patients have low blood complement C3 levels

- Type II mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (dense deposit disease). 75% have low C3 levels. And 70-80% of patients also have an antibody called ‘C3 nephritic factor (C3NeF)’

- Type III mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis.

Neither complement nor C3NeF levels relate to disease activity.

Note. The differences between the kidney biopsies are subtle and beyond the scope of this article.

Treatment

The effectiveness of various treatments tried in MCGN is difficult to assess because of the small patient numbers in short-term studies, in the published research.

The larger trials carried out to date have been ‘uncontrolled’ – i.e. did not compare the treatment to patients that did not have the treatment.

Therefore, treatment strategies – especially for for primary MCGN – are controversial and have included steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, antiplatelet drugs, plasma exchange (a bit like dialysis of the immune system) and biological agents (modern ‘magic bullet’ treatments).

But there are things that can be done. Treatments may include:

- Medicines – such as ACE inhibitors (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) and ARBs (angiotensin receptor blockers) and SGLT2is (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors) to control blood pressure and protein loss

- Diuretics (water tablets) – to reduce oedema

- Steroids – may be used to treat nephrotic syndrome. However there is little evidence that they have much effect

- Other immunosuppressants (drugs that dampen down the immune system) – are sometimes used. Again the evidence for their use is lacking

- Cholesterol lowering drugs – may be necessary

- Blood thinning drugs – may be needed to prevent blood clots

- Dialysis and/or kidney transplantation. MCGN can recur in a kidney transplant

- Recurrence of MCGN in kidney transplants – treatment is uncertain, but plasma exchange may be useful in patients whose renal function deteriorates rapidly; whereas a drug called rituximab seems to be an effective in patients with cryoglobulinaemia.

For secondary causes, it is important to treat (and remove, if possible) the underlying cause – e.g. treat an infection such as hepatitis B/C or infective endocarditis.

Prognosis (outlook)

If the MCGN is primary (no known cause), the outcome is not usually good. 50% of patients progress to end-stage kidney failure (ESRF) and need dialysis (and/or a kidney transplant) within 10 years (and 90% at 10 years). But it is 15% at 10 years, in the absence of nephrotic syndrome – i.e. lower levels of protein in the urine are a good sign as in most causes of CKD. Spontaneous remission or improvement can occur (in less than 10% of cases).

Type II MCGN carries a worse outlook than Type I.

The recurrence rate of the disease in a kidney transplants is high; 30% of patients with type I MCGN, and (unfortunately) 90% of those with Type II.

Whereas if MGGN is secondary (associated with another condition; e.g. any of the ones listed above), it is usually resolved (or partially) by successfully treating the associated condition or disease.

For example, if MCGN is associated with Hepatitis B or C viral infection, it tends to resolve either spontaneously or following treatment of the virus.

Summary

We have described what is mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN). We hope you have found it helpful.

Other resources

These are good review articles (for health professionals): Alchi, 2010 and Salvadori et al, 2016.

The latter one proposed a new classification system.

The UK Kidney Association also debates the newnomenclature using the phrase C3 nephropathy (or C3GN).

What is chronic glomerulonephritis?

What is minimal change disease?

What is membranous nephropathy?

What is FSGS?

What is IgA nephropathy?

What is post-infectious glomerulonephritis?

What is rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis?

Last Reviewed on 24 May 2024